Dallas Artist Helps Writers Transform Personal Stories into Sculptural Books

At the age of 4, Alisa Banks received her first book — a thick volume of Mother Goose nursery rhymes given to her by her aunt. She was mesmerized by the colorful images and mysterious letters.

“I understood them as codes that could unlock the stories,” Banks writes in her essay “Reading Roots.”

“No matter how many times I turned the pages and stared, or how fervently I wished, the code could not be broken.”

Now, decades later, Banks has built an artistic practice around breaking different kinds of codes, exploring what she calls “root reading” — a way of understanding histories and stories that were systematically denied access to Western literacy. As a book artist whose work is housed in the Smithsonian Institution, the U.S. Library of Congress, and the British Library, Banks creates sculptural books that challenge our assumptions about what reading means and whose stories deserve to be preserved.

This April, she brings that practice to BARN’s Handwork Week with “Speak Your Piece: Artist’s Books with Meaning,” a five-day intensive workshop that guides participants in transforming personal stories into three-dimensional, tactile narratives.

“Handwork connects us to each other, to the environment, to the planet in a deeper way, both physically and mentally.”

The Materials Remember What Words Forget

Banks’s path to book arts took unexpected turns. She initially enrolled at university to study fashion, but switched to medical laboratory science during her second year. After earning her bachelor’s degree in medical laboratory science from Oklahoma State University, she worked as a hospital lab scientist for years before returning to school for her master of fine arts in Visual Art from Texas Woman’s University.

“A lot of people think it’s unusual, but I’ve met a lot of scientists who are interested in the arts, if not outright artists themselves,” Banks has said. “We think of science as being very strict, but there’s some creative aspects to it.”

But the foundation for her artistic practice had been laid much earlier. Banks grew up surrounded by creative women who were always sewing, doing embroidery, and crocheting. She remembers being a little girl, sitting quietly on the floor between her mother’s knees as her mom did her hair and told family stories, sometimes with the help of her aunt and grandmother. These moments of transformation became central to how Banks thinks about art and memory.

Throughout her career as a medical lab scientist, Banks continued to make art on the side, landing solo shows and contributing pieces to group shows over the years. Now retired from laboratory work, she can focus on her art full time. Her work has been exhibited internationally and is housed in major collections including the Smithsonian Institution, the U.S. Library of Congress, the Schomburg Center, and the British Library. She also is an exhibiting artist for the Art in Embassies program, displaying her work in U.S. Embassies globally.

Root Reading: Reconciling Practice with History

Banks investigates connections between contemporary culture, her Louisiana Creole heritage, and the African diaspora through what she calls the lenses of home, terrain, and the body, using Southern Louisiana as a point of entry. Her sculptural artist books, mixed media work, and textile collages often incorporate fibers and found materials that reference traditional craft forms.

Banks approaches all of her work with one big question in mind: “What is home?” She grew up in a military family that moved frequently and never felt a strong connection to her hometown roots in Louisiana. In her adult life, much of her artistic journey has grown from a desire to know more about the place she came from. She explores the question in sculptural books, textile collage and mixed media that incorporates found materials, like hair, cloth, plants, soil gathered from her family’s Louisiana farmstead, and traditional craft techniques.

“Black women pass on family histories, despite broadly having been denied access to reading and writing,” Banks explained at the opening of her “Unerased” exhibition at Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. “The act of hair culture, caring for hair, allowed one to pass on history. That’s something that’s common throughout the many diasporas. My experience is with the African diaspora.”

Banks calls her process of reconnecting with her personal history “root work.” “Root work for me is a way to reconcile with my semi-nomadic background. I speak at a distance from my roots, but I am still connected to them,” she said.

History of a People is a unique artist’s book that traces African American history and culture through scent. Each of the six bottles (or chapters) holds a custom blended scent that corresponds to the cultural landscape of selected historical periods: Roots, Journey, Arrival, Harrow, Protest, and Visioning.

“I feel like what I’m doing is a form of resistance,” she told a Colorado College audience. “Making sure the stories go on and understanding what actually is instead of the sound bites is a way to keep straight on the path.”

Books That Require Your Participation

Banks’s artist books aren’t meant to be merely looked at; they are meant to be experienced. They demand interaction, slowing readers down through deliberate design choices that mirror the rituals of care and knowledge-transmission she witnessed growing up.

“The flexibility of the artist book can accommodate both general and esoteric cues,” Banks explains.

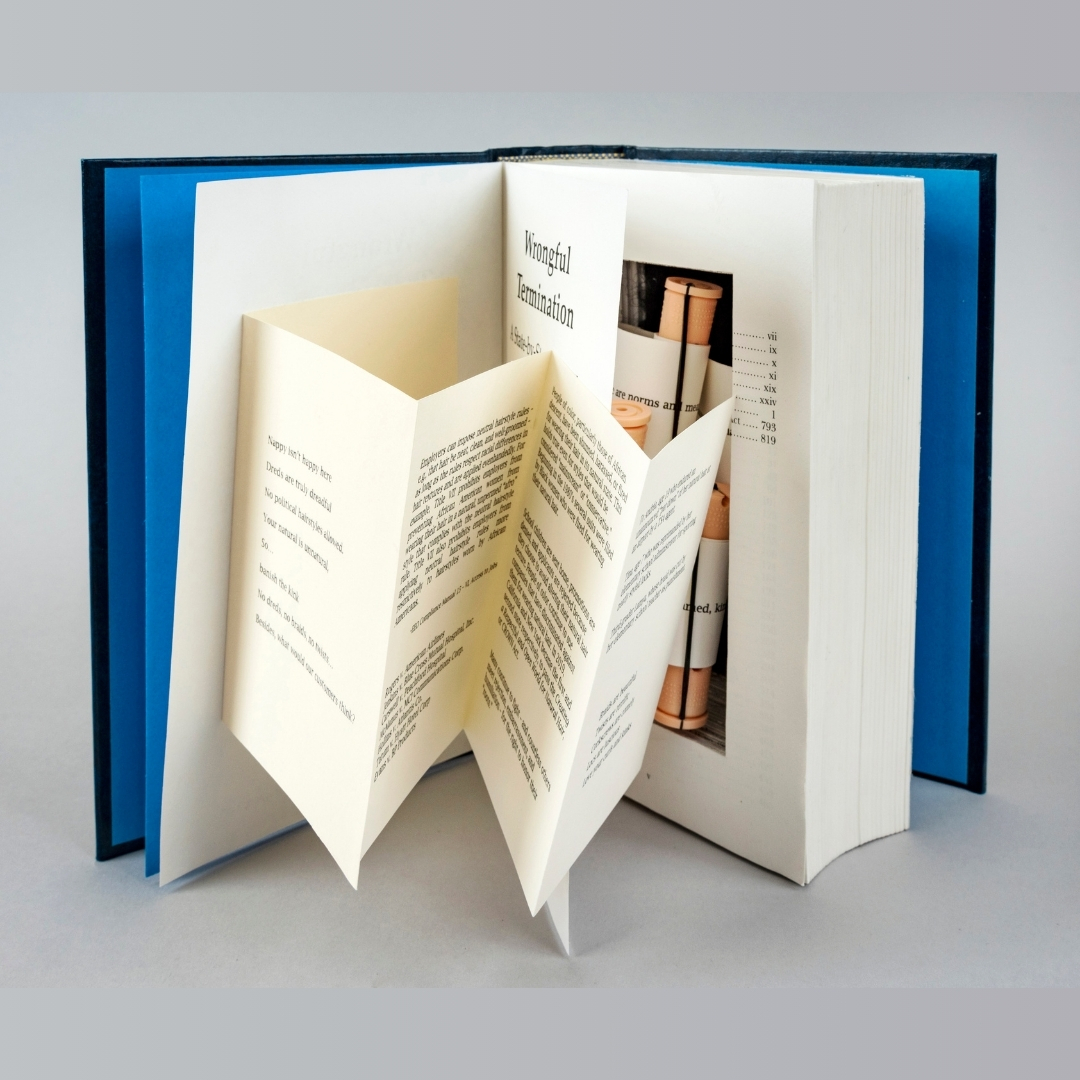

Consider “Wrongful Termination,” an altered law book addressing race-based employment discrimination. To read it, viewers must unroll text from plastic hair curlers — an intimate act that invites participation in a hair-care ritual while contemplating negative comments about natural Black hair. Hair is attached inside the book cavity, almost out of reach, alluding to the inappropriateness of strangers asking to touch Black hair.

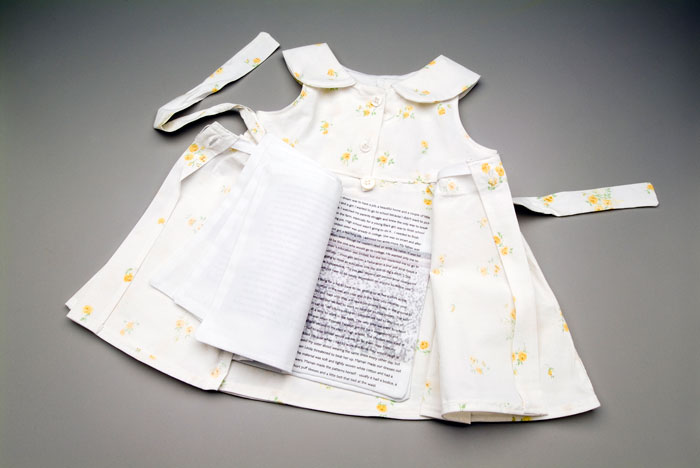

Or “Island Girl,” a cloth dress embedded with Louisiana Creole phrases that tells a story of rejection, acceptance, and cultural pride. The dress form itself reminds readers of how economic factors and adult attitudes affect children’s relationship to their heritage.

“Emergence,” created in three parts with two drum–leaf–bound books titled “Litany“ and “Election,” and a carved candle, referencing the Roman Catholic Mass.

Teaching as Cultural Transmission

Banks’s approach to teaching artist books extends from her belief that charged materials and deliberate structures can help people tell stories that conventional literacy might not serve.

“I hope participants will feel empowered to share something that is meaningful for them,” she says, “that they understand if something is important to them, then there are others who will be interested.”

Her five-day BARN workshop (April 27-May 1, 2026) guides participants through writing, brainstorming, and project planning to develop content for their books, with daily personal feedback. The technical skills covered — bookbinding (accordion and pamphlet styles), frottage/collagraphy, monotype printing, book cloth making — serve the larger goal of helping participants discover what form their stories need to take.

“By starting the workshop with a planned subject, participants will be able to really focus on various ways to layer their ideas,” Banks explains. “I’m really excited to be guide and witness their unfolding.”

Participants should arrive with “a theme or concept you’re excited about, along with any materials or ephemera you feel drawn to use.” By week’s end, they’ll have completed a unique artist’s book or prototype centered on their chosen theme.

Banks emphasizes that the materials themselves can unlock unexpected connections. She makes paint from soil gathered at her family’s Louisiana farmstead, adding liquid from boiled acorns, walnut hulls, and indigo pigment — each ingredient connecting to place, history, and root. When she sews plants onto cloth pages or incorporates hair into book structures, she’s building what she calls “a bridge to my ancestors.”

The Political Is Structural

Banks’s recent exhibition “Unerased” at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center demonstrates how her work operates on multiple levels simultaneously — personal, cultural, historical, and political.

“I feel like what I’m doing is a form of resistance,” she told a Colorado College audience. “Making sure the stories go on and understanding what actually is instead of the sound bites is a way to keep straight on the path.”

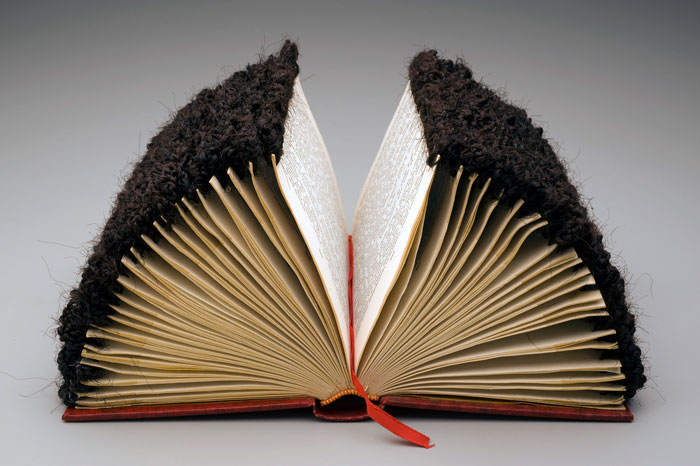

This isn’t metaphorical resistance. Banks’s work intervenes in ongoing struggles over whose knowledge counts, whose literacy matters, and whose stories deserve preservation. Her “Edges“ series — altered Spanish-language books featuring hair attached in patterns based on braided hairstyles of African ancestry — was created in direct response to anti-immigration rhetoric. The series acknowledges “not only the creativity, activity, and life that occur on and outside the margins of mainstream culture, but also the effect marginalized communities have on mainstream culture.”

She points out that common literacy — the ability to read and write in the dominant language — is a relatively recent achievement for most families, including those who can trace their histories back to early European colonization of North America. For many, other forms of reading have always been primary: reading the stars for navigation, reading faces and body postures for safety, and reading hairstyles for social and political affiliation.

“To a person unfamiliar with them, a certain series of marks, for example, might appear random or accidental,” Banks writes. “But for the initiated, there is an understanding of a sign or symbol often overlooked by others.”

Distance as a Form of Seeing

Banks speaks and writes candidly about her position relative to the Louisiana Creole culture she explores. Raised in a military family that moved constantly, hearing but not fully learning her parents’ Creole language, she describes herself as “belonging to, but remaining on, the outside.”

Rather than claim an authenticity she doesn’t possess, Banks examines how distance itself can become a tool for understanding. “Distance (that is, being on the outside) can bring a peculiar view to something observed from afar,” she writes. “One can grasp a kernel of the soul of belonging to a culture — the traditions and ways of living that persist in a community living outside of the mainstream.”

This intellectual honesty — refusing easy claims while still asserting connection — strengthens her work. She’s not performing culture for outsiders or claiming insider status she hasn’t earned. Instead, she’s doing the difficult work of piecing together fragments, reading what remains, honoring what was carried forward despite systematic efforts at erasure.

“Though I can claim no hometown for myself, having traveled from station to station because of my dad’s career, my experience is not too dissimilar from those who can claim otherwise,” Banks observes, “because from a cultural aspect, we are all to some degree removed from root.”

The Magic Remains

Throughout Banks’s essay on root reading, a particular word recurs: magic. The magical transformation she witnessed as her mother cut and sewed fabric. The magic of marks on paper, unlocking hidden information. The magic of creating physical work by hand from raw materials.

This isn’t childish fancy. For Banks, the magic lies in how materials and processes can carry meaning across time and displacement, how hands can remember what official histories have forgotten, how cloth, hair, and plants can testify to survival, creativity, and resistance.

Even now, as Banks’ work is exhibited internationally and housed in major collections, the transformation of raw materials into vessels for story remains as powerful as it was when she first watched her mother work magic at the dining room table.

“Handwork connects us to each other, to the environment, to the planet in a deeper way, both physically and mentally,” she says.

Some stories can’t be contained by conventional pages. They need to unfold — literally and figuratively — in the reader’s hands.

Learn more about Alisa Banks’s work at alisabanks.com or read her essay “Reading Roots” published in Openings: Studies in Book Art.

“Speak Your Piece: Artist’s Books with Meaning” runs April 27–May 1, 2026 at BARN. Tuition assistance is available. For more information about Handwork Week 2026 and to register, visit bainbridgebarn.org/handwork2026

Follow Us