By day, Brian Gillespie manages the development team for Rhino 3D, the industry-standard modeling software used in aerospace, automotive, and architectural design. But step into his Ballard workshop in Seattle, and you’ll find him doing something that requires no screens at all: folding thousands of precisely cut paper elements into abstract sculptures that dance with light and shadow.

“Working with my hands gives my mind a rest,” Gillespie explains. “There’s nothing more relaxing than spending time making—but only when my hands and body are intimately involved.”

This spring, Gillespie will share that philosophy with students at BARN in his workshop “Modern Mobiles: Balancing Digital and Hand Craft,” part of Handwork Week at BARN, a five-day intensive workshop series that celebrates traditional craft alongside contemporary innovation.

His class offers participants a chance to explore kinetic sculpture through the lens of one of America’s most revolutionary artists: Alexander Calder.

“Working with my hands gives my mind a rest,” Gillespie explains. “There’s nothing more relaxing than spending time making—but only when my hands and body are intimately involved.”

The Kinetic Sculpture Revolution

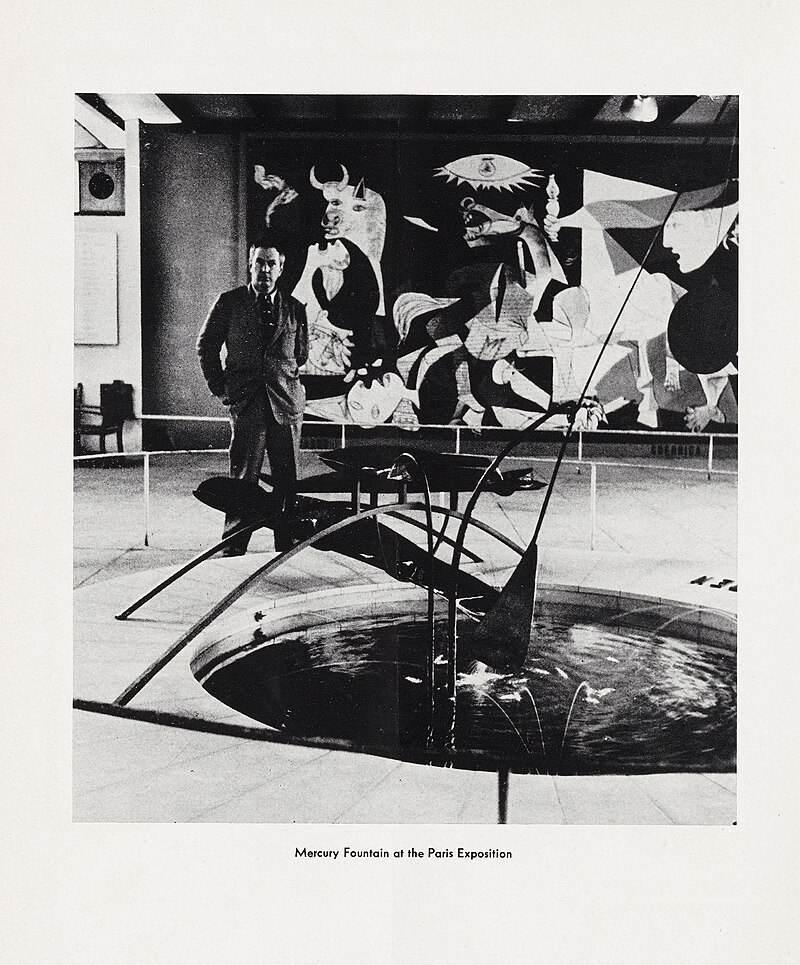

Alexander Calder (1898-1976) revolutionized sculpture by inventing the mobile—kinetic sculptures suspended in space that move in response to air currents. The term was coined by Marcel Duchamp in 1932 as a pun in French meaning both “motion” and “motive”. Before Calder, sculpture was static. After him, it breathed.

Calder transformed sculpture from a static art form into a dynamic interplay of movement, volume, and vibrant color. His shapes, often evoking leaves or petals, are suspended from long metal rods balanced with precision, swaying with the wind. What made his kinetic sculpture so radical wasn’t just the movement itself, but the way he entrusted his creations to the environment, allowing each mobile to perform differently depending on air currents, light, and space.

Calder studied engineering at the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey before moving to Paris to study art. That engineering background became the foundation for his artistic breakthrough. In Europe, he entertained his wide circle of friends, including artists Joan Miró, Marcel Duchamp, and Piet Mondrian, with articulated toys, circus figures, and wire sculptures.

“Alexander Calder invented the mobile as a sculptural form in the 1930s,” Gillespie explains in his class description. “Mobiles are constantly in motion, rearranging and recomposing based on the effects of the wind and human touch. This added element of time differentiated Calder’s work from all other sculptural forms of the time.”

Hugo P. Herdeg

From Software to Kinetic Sculpture

Gillespie’s path to exploring Calder’s legacy mirrors the artist’s own journey from engineering to art. For over 30 years, Gillespie has written software and now manages the Rhino development team at McNeel, designing user interaction workflows, business processes, and internal communication tools. His technical expertise in 3D modeling gives him unique insight into the mathematical precision underlying Calder’s seemingly spontaneous mobiles.

“Making sense of all the angles requires a computer,” Gillespie says about his own work. “3D modeling lets me draw these complex compositions. My creative expression includes making tools to model, unfold, mark, score, and cut the paper precisely. Once cut, my hands fold and assemble the final work.”

As a sculptor, programmer, and engineer who creates using wood, clay, metal, glass, and paper, Gillespie has been a member of the Rhino software development team since its inception, witnessing firsthand how computer-aided design has transformed the way humans create things. He uses digital fabrication tools, including milling machines, 3D printers, laser cutters, plasma cutters, and vinyl cutters, to design and create his work.

“I’m most interested in work that straddles the technical and the human—work that is difficult or impossible to do by hand, yet also impossible to completely automate,” he explains. It’s this balance that makes his exploration of kinetic sculpture particularly compelling.

Cut, Folded, and Assembled Paper, Gold Foil

“My creative expression includes making tools to model, unfold, mark, score, and cut the paper precisely. Once cut, my hands fold and assemble the final work.”

A Deep Dive into Mobile Making

Gillespie’s five-day intensive workshop offers a rare opportunity to gain a profound understanding of what makes kinetic sculpture work. “Often seen hanging above cribs in nurseries, beautiful mobiles are anything but child’s play to create,” he notes. “In this class, you’ll experience what it might have been like for Calder to invent, create, and enjoy this dynamic sculptural form.”

Having studied many of Calder’s works and built his own mobiles, Gillespie has identified the essential challenges of creating successful kinetic sculpture:

Mechanical balance: Achieving balance with different objects in space requires practice, planning, and sometimes mathematical calculations.

Visual balance: Adding visual harmony through size, color, and proximity compounds the challenge.

Grace: The wires that support the weighted elements must make visual sense—how they curve, where they point, and where they attach all influence the grace and visual balance.

Dance: The movement itself must be pleasing, with opportunities for refinement and adjustment.

The workshop begins with quick experiments using easy-to-work materials, helping participants gain intuition for balancing kinetic sculpture. “Working quickly will help us develop hand skills of working with wire, mechanical connections between materials, and how to connect elements of the mobile together,” Gillespie explains. “We’ll strive for visual balance and grace as we assemble quickly, allowing our mistakes to blossom into effective creations later.”

Merging Digital Tools with Hand Craft

What sets Gillespie’s approach apart is the seamless integration of computational design with traditional craft. Students will use Rhino to design and draw shapes, then cut them out using a laser cutter. As the class progresses, they’ll dive into the math and physics of balance, learning to predict how forms will equilibrate. Gillespie will demonstrate how to use Rhino and Grasshopper—a visual programming environment—to aid in the balancing act, sharing these tools with participants.

“We’ll dance back and forth between the computer and hand craft as we hone our compositions to achieve visual balance and graceful wire structures,” he says. After a few days of experimentation, students will work with larger gauge wire and materials such as painted plywood or acrylic sheet, choosing to work either digitally or intuitively to build one or more final mobiles. They can also incorporate found objects or 3D-printed elements into their creations.

The workshop concludes with an exposition of all the kinetic sculptures hanging and dancing in BARN’s Tech Lab—a fitting tribute to Calder’s vision.

Handwork in the Digital Age

Gillespie’s participation in Handwork Week is particularly fitting for an initiative that celebrates the importance of handmade work in American culture. The national Handwork: Celebrating American Craft 2026 is a Semiquincentennial collaboration led by PBS’s Craft in America and the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery, bringing together over 200 organizations to showcase craft traditions throughout 2026.

“Working with our hands and our body soothes me and brings me joy,” Gillespie reflects. “I believe we need more soothing, connection with ourselves, and joy in America today.” In an era where much creative work is done on screens, his perspective offers a vital counterbalance. The computational tools don’t replace handwork—they enhance it, allowing makers to explore kinetic sculpture forms and movements that would be impossible to calculate manually, then bringing those visions to life through patient, meditative construction.

His work creates what he calls “abstract, geometric, and sometimes functional art”—pieces inspired by “light, shadow, form, and color” as well as “shapes that are difficult or impossible to do by hand, and also difficult or impossible to completely automate.” That sweet spot between human and machine capability is where innovation in kinetic sculpture happens.

A Calder Connection

There’s even a surprising regional connection to Calder’s story. In 1922, Calder worked as a timekeeper in a logging camp in Independence, Washington, during the early stages of his career. The region that would later become home to companies like McNeel and makers like Gillespie once hosted the young artist who would revolutionize the art of sculpture.

For those interested in exploring kinetic sculpture at the intersection of craft, computation, and movement, Gillespie’s workshop offers a rare deep dive. Participants should have strong hands for bending and forming wire, and will need to bring a laptop that can run Rhino 8 (a license will be provided during class). Ages 14 and up are welcome.

In the end, Gillespie’s workshop offers something Calder would have appreciated: a chance to understand the engineering principles that make kinetic sculpture move, balanced with the irreplaceable experience of creating with your own hands. As Gillespie puts it: “Sitting back and watching a machine or being in the presence of a noisy tool can often be stressful and tiring. Working with my hands and my body soothes me and brings me joy.”

It’s a philosophy that would make Calder smile.

“Modern Mobiles: Balancing Digital and Hand Craft” runs April 27–May 1, 2026 at BARN. Registration is $1,260 for members and $1,390 for guests. Tuition assistance is available. For more information about Handwork Week 2026 and to register, visit bainbridgebarn.org/handwork2026

Follow Us