The phrase “systematic creativity” might seem an oxymoron, but for glass artist Nathan Sandberg, it’s been a life’s work.

The Portland-based glass artist has spent decades exploring the creative potential in systematic processes that allow for subtle variations and unexpected discoveries. For Sandberg, the journey of creation is as significant as the final piece.

“I think repetition in the process is almost more attractive than the finished thing,” says glass artist Nathan Sandberg.

His fascination with materials, particularly glass, drives him to push boundaries, transforming traditional techniques into novel methods. Sandberg believes in the power of patience and persistence, often spending years refining a single technique to unlock its full potential.

“Materials have always been interesting to me,” Sandberg reflects. (Even as a young kid, he was digging clay out of the banks of Lake Erie and “firing” crude hand-built pots next to a campfire.) It was this innate curiosity that led him to explore the mesmerizing possibilities of glass.

Sandberg first stumbled upon glasswork while studying photography and ceramics in Eastern Washington. There, he learned that the Pratt Fine Arts Center was offering classes in glass, an unusual offering at the time.

“I didn’t know anything about it – it seemed super special and magical to learn how to work with this crazy material.”

He took a bead-making class and then a class in the hot shop. He was hooked and transferred to Southern Illinois University, where he could earn a BFA in glass and ceramics. After graduation, he got a job in the research and education department at the Bullseye Glass Factory in Portland.

“That is where I met the Vitrigraph kiln.”

The Vitrigraph is an elevated kiln that holds a flowerpot full of glass. Upon heating the kiln, the glass in the pot melts and drips down through the hole in the pot and the bottom of the kiln, creating long, thin strands called stringers. Artists use these stringers to make patterns or designs in their glasswork. It’s a bit like making glass spaghetti.

For Sandberg, the Vitrigraph was a way to systematize some of the techniques he’d played around with in the hot shop in college, looking for ways to make murrine – a centuries-old decorative glasswork technique that creates distinctive patterns. (“I was making … a mess, honestly,” he says about those early experiments.)

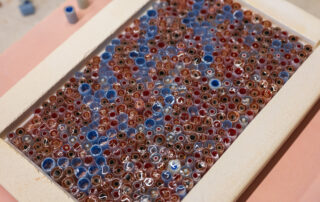

Murrine rods are made by layering different colored glass and then stretching the hot glass into a cane. When you slice this cane, each cross-section shows the same pattern. Glass artists use these slices in various ways: fusing them together to make patterned sheets, embedding them in other glass objects, or using single slices as decorative elements.

Sandberg has developed Vitrigraph techniques to make beautiful and complex murrine patterns.

At Bullseye, Sandberg wondered if the Vitrigraph could be used to make these beautiful and complex patterns. He started experimenting, developing techniques he would perfect over the next nine years. He tried different temperatures, tried loading the class differently, observed how the glass behaved when he coaxed it out with needle-nosed pliers versus when he left it to the slow drip of gravity. In the process, he learned a lot about glass viscosity, softness, stiffness, and behavior under different conditions. Now, he teaches those techniques in workshops worldwide, including recent intensives at BARN, teaching techniques like Vitrigraph Murrine and Flow Wedges.

Sandberg’s own work often consists of numerous small elements combined into striking compositions. Each piece, while born from a repetitive process, carries its own unique character. “I think repetition in the process is almost more attractive than the finished thing,” he says.

“There’s just kind of some comfort in lining up all the steps, knowing what they are, knowing what’s going to happen next, and then in the end they all connect together. This methodical approach, far from stifling creativity, seems to enhance it, allowing Sandberg to push the boundaries of the possible.

His work, found in collections worldwide, speaks to the power of finding creativity within structure. It reminds us of the beauty that can emerge from repetition. In his hands, glass becomes more than a medium—it becomes a reflection of the intricate patterns and rhythms that underpin our world.

Follow Us